Types of AI Agents: Definitions, Roles, and Examples

Summary

- AI agents are moving from prediction to execution, taking real actions using reflex, model-based, goal-based, utility-based and learning approaches that trade predictability for adaptability.

- The right agent depends on the task: simple agents suit stable, repetitive work, while dynamic environments may need planning or learning, but added autonomy often increases risk and complexity.

- The most successful production agents are hybrids, combining reflexes for safety, planning for flexibility and limited learning for adaptation, guided by governance, clear trade-offs and gradual scaling.

AI agents are moving from novelty to necessity. What began as simple automation and chat-based assistants is evolving into systems that observe their environment, decide what to do next and take action across real workflows. These agents execute jobs, call tools, update systems and influence decisions that once required human judgment.

As AI systems take action, the stakes increase. Errors can cascade through downstream systems and produce outcomes that are difficult to trace or reverse. This shift turns agentic AI into a system design challenge, requiring teams to think earlier about autonomy, control, reliability and governance.

At the same time, the language around AI agents has become noisy. Depending on the source, there are four types of agents, or five, or seven—often reflecting trends rather than durable design principles. This guide takes a pragmatic view. Rather than introducing another taxonomy, it focuses on a stable framework for understanding AI agents and uses it to help you reason about trade-offs, avoid overengineering and choose the right agent for the problem at hand.

Why agent types matter in practice

From prediction to execution

AI agents matter because AI systems are no longer confined to analysis or content generation. They increasingly participate directly in workflows. They decide what to do next, invoke tools, trigger downstream processes and adapt their behavior based on context. In short, they act.

Once AI systems act, their impact compounds. A single decision can influence multiple systems, data sources or users. Errors propagate faster, and unintended behavior is harder to unwind. This is what distinguishes agentic AI from earlier generations of AI applications.

As a result, teams are rethinking where AI fits in their architecture. Agents blur the line between software logic and decision-making, forcing organizations to address reliability, oversight and control much earlier than before.

How agent types shape design decisions

The value of classification shows up in real design choices. Agent types are not abstract labels; they encode assumptions about how decisions are made, how much context is retained and how predictable behavior needs to be. Choosing an agent type is choosing a set of trade-offs.

A reflex-based agent prioritizes speed and determinism. A learning agent adapts over time but introduces uncertainty and operational cost. Without a clear framework, teams often default to the most powerful option available even when the problem does not require it.

Classification provides a shared language for these decisions. It helps teams align expectations, reason about failure modes and avoid overengineering. In a fast-moving landscape full of new tools and labels, a stable mental model allows practitioners to design agent systems deliberately rather than reactively.

The building blocks of an AI agent

How agents perceive and act

An AI agent exists in an environment and interacts with it through perception and action. Perception includes signals such as sensor data, system events, user inputs or query results. Actions are the operations the agent can take that influence what happens next, from calling an API to triggering a downstream process.

Between perception and action sits state. Some agents rely only on the current input, while others maintain internal state that summarizes past observations or inferred context. Effective agent design starts with the environment itself: fully observable, stable environments reward simpler designs, while partially observable or noisy environments often require memory or internal models to behave reliably.

Autonomy, goals and learning

Autonomy describes how much freedom an agent has to decide what to do and when to do it. An agent’s decision logic — the rules, plans or learned policies that map observations to actions — determines how that freedom is exercised. Some agents execute predefined actions in response to inputs, while others select goals, plan actions and determine when a task is complete. Autonomy exists on a spectrum, from low-level agents that react directly to inputs to higher-level agents that plan, optimize or learn over time.

Goals and learning increase flexibility, but they also add complexity. Goal-driven agents must adjust plans as conditions change. Learning agents require ongoing training and evaluation as behavior evolves. Each step toward greater autonomy trades predictability for adaptability, making clear boundaries essential for building agents that remain understandable and trustworthy in production.

The five core AI agent types

The five core AI agent types describe five fundamental ways agents decide what to do: reacting to inputs, maintaining internal state, planning toward goals, optimizing trade-offs and learning from experience. This framework persists because it describes decision behavior rather than specific technologies. By focusing on how an agent reacts, reasons, optimizes or adapts — not on the tools it uses or the roles it plays — it continues to apply to modern systems built with large language models, orchestration layers and external tools.

1. Simple reflex agents

Simple reflex agents operate using direct condition–action rules. When a specific input pattern is detected, the agent executes a predefined response. There is no memory of past events, no internal model of the environment and no reasoning about future consequences. This simplicity makes reflex agents fast, predictable and easy to test and validate.

Reflex agents work best in fully observable, stable environments where conditions rarely change. They remain common in monitoring, alerting and control systems, where safety and determinism matter more than flexibility. Their limitation is brittleness: when inputs are noisy or incomplete, behavior can fail abruptly because the agent lacks contextual state.

2. Model-based reflex agents

Model-based reflex agents extend simple reflex agents by maintaining an internal representation of the environment. This internal state allows the agent to reason about aspects of the world it cannot directly observe. Decisions remain rule-driven, but those rules operate over inferred context rather than raw inputs alone.

This approach improves robustness in partially observable or dynamic environments. Many practical systems rely on model-based reflex behavior to balance reliability and adaptability without introducing the unpredictability of learning.

3. Goal-based agents

Goal-based agents represent desired outcomes and evaluate actions based on whether they move the system closer to those goals. Rather than reacting immediately, these agents plan sequences of actions and adjust as obstacles arise. Planning enables flexibility and supports more complex behavior over longer horizons.

Planning also introduces cost and fragility. Goals must be clearly defined, and plans depend on assumptions about how the environment behaves. In fast-changing settings, plans often require frequent revision or fallback logic. Goal-based agents are powerful, but they require careful design discipline to avoid unnecessary complexity.

4. Utility-based agents

Utility-based agents refine goal-based reasoning by assigning value to outcomes rather than treating success as binary. Actions are chosen based on expected utility, allowing the agent to balance competing objectives such as speed, accuracy, cost or risk.

The strength of utility-based agents is transparency. By encoding priorities directly, they expose decision logic that would otherwise be hidden in heuristics. The challenge lies in defining utility functions that reflect real-world priorities. Poorly specified utility can lead to technically optimal but undesirable behavior.

5. Learning agents

Learning agents improve their behavior over time by incorporating feedback from the environment. This feedback may come from labeled data, rewards, penalties or implicit signals. Learning allows agents to adapt in environments that are too complex or unpredictable to model explicitly with fixed rules.

At the same time, learning introduces uncertainty. Behavior evolves, performance can drift, and outcomes become harder to predict. Learning agents are best used when adaptability is essential and teams are prepared to manage that complexity.

Emerging and hybrid AI agent patterns

Multi-agent systems

As AI agents are applied to larger and more complex problems, single-agent designs often fall short. Multi-agent systems distribute decision-making across multiple agents that interact with one another. These agents may cooperate toward shared goals, compete for resources or operate independently within a distributed environment. This approach is useful when work can be decomposed or parallelized.

The trade-off is coordination. As the number of agents grows, the risk of conflicting actions, inconsistent state and unintended emergent behavior increases, making clear communication and coordination mechanisms essential for reliability and predictability.

Hierarchical agents

Hierarchical agents add structure by layering control. A higher-level agent plans, decomposes objectives or provides oversight, while lower-level agents focus on execution. This supervisor–sub-agent pattern helps manage complexity by separating strategic decisions from operational ones.

Hierarchies can improve clarity and control, but they also introduce dependencies. If responsibilities between layers are poorly defined, failures or incorrect assumptions at higher levels can cascade through the system.

Hybrid and role-based agents

Most production agents are hybrids. They combine reflex behavior for speed and safety, planning for flexibility and learning for adaptation. This blended approach allows systems to balance reliability with responsiveness as conditions change.

Many modern labels describe functional roles rather than behaviors. Terms like customer agents, code agents, creative agents or data agents describe what an agent does, not how it decides. Trends such as LLM-based agents, workflow agents and tool-using agents reflect new interfaces and capabilities that are still best understood through classical agent behaviors.

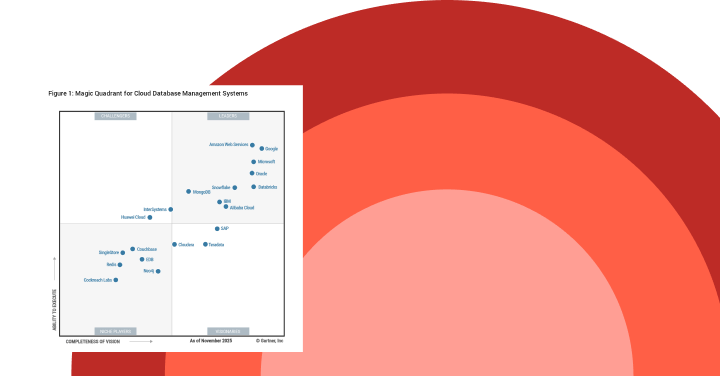

Gartner®: Databricks Cloud Database Leader

Choosing the right AI agent for your use case

Match agent design to reality

Choosing an AI agent type should start with the problem, not the tools. Different agent designs assume different levels of predictability, control and risk. When those assumptions don’t match reality, even sophisticated agents fail in ways that are hard to diagnose.

Highly repetitive, well-defined tasks usually benefit from simpler agents. As tasks become more open-ended or require sequencing, goal-based or utility-based agents become more appropriate. A common mistake is assuming complexity automatically requires learning.

Environment dynamics matter just as much. In stable environments, simpler agents can remain effective for long periods. In dynamic environments, adaptability becomes valuable — but only with feedback loops and oversight. Interpretability is another constraint. If decisions must be explained or audited, predictable behavior often matters more than flexibility.

When learning helps — and when it hurts

Learning agents are most useful when explicit rules are impractical or when performance depends on patterns that only emerge through experience. Personalization and reinforcement learning scenarios often fall into this category.

That adaptability comes at a cost. Learning introduces operational overhead and evolving behavior that complicates testing and governance. In largely stable environments, learning can add risk without meaningful benefit.

A practical heuristic helps clarify these trade-offs. If you can define the rules clearly, don’t learn. If you can define the goal clearly, don’t optimize. If you can define the utility clearly, optimize deliberately. Learning should be a deliberate choice, not a default.

Warning signs of a poor fit include unstable outputs, excessive retraining cycles, unclear failure modes and difficulty explaining why an agent behaved a certain way. These symptoms often indicate that the agent type is misaligned with the problem, rather than a flaw in the underlying models or tools themselves.

How AI agent types show up in practice

Automation, control and planning

AI agent types are easiest to understand through the problems they solve in practice. Reflex agents remain foundational in automation and control systems where speed and predictability matter most. Simple condition–action behavior underpins alerting and monitoring workflows because responses must be immediate and consistent.

Model-based reflex agents extend this pattern to environments with incomplete or delayed information. By maintaining internal state, they support more robust behavior in domains like robotics, navigation and long-running software workflows, where agents must infer what is happening beyond raw inputs.

Goal-based agents are common in planning and coordination scenarios. Scheduling work, sequencing tasks or routing requests through multi-step processes benefits from agents that reason about future states, particularly when objectives are clear and environmental assumptions remain stable.

Optimization and learning-driven systems

Utility-based agents dominate optimization-heavy applications such as recommendation systems and resource allocation. Utility functions make trade-offs explicit, allowing these systems to balance competing objectives and be tuned and evaluated more transparently.

Learning agents underpin adaptive decision systems where patterns evolve over time. They become valuable when static rules break down, but they also require ongoing evaluation and retraining to remain reliable.

Agents in business and analytics workflows

In business and analytics workflows, modern agent systems increasingly combine multiple approaches. Agents may plan queries, select tools, retrieve data and trigger downstream actions. In software development workflows, agents increasingly assist with tasks such as navigating large codebases, running tests, proposing changes or coordinating pull requests across systems. At this stage, observability, governance and control matter more than clever behavior — especially when governing and scaling production AI agents becomes a requirement rather than an afterthought.

Challenges, limitations and misconceptions

Why agent classifications diverge

AI agent lists often differ because they answer different questions. Some frameworks classify agents by decision behavior, others by system architecture and others by application role. When these perspectives are mixed, the number of “types” grows quickly without adding clarity.

This confusion is compounded by marketing-driven labels such as “big four agents” or role-based terms like coding agents or customer agents. These labels describe how agents are positioned rather than how they decide or behave, which makes comparisons misleading.

More autonomy isn’t always better

Another common misconception is that more autonomy automatically produces better systems. In practice, increased autonomy almost always introduces additional complexity. Highly autonomous agents are harder to test, predict and constrain. For many use cases, simpler agents outperform more advanced ones because their behavior is easier to reason about and control.

Learning agents introduce their own risks. As behavior evolves over time, outcomes can become unpredictable, especially when data quality degrades or feedback loops form. Ongoing maintenance overhead — such as retraining, evaluation and monitoring — is also often underestimated during early experimentation.

Misunderstandings about intelligence further complicate matters. Agents that appear intelligent often rely more on structure, constraints and careful design than on sophisticated reasoning. Effective agent design is not about maximizing autonomy or intelligence, but about balancing control, flexibility and cost. Teams that make these trade-offs explicit are far more likely to build agents that succeed in production over time.

Where agentic AI is headed

Agentic AI is evolving quickly, but the direction is becoming clearer. Large language models are changing how agents reason, interact with tools and work with unstructured inputs, making them more flexible and expressive. What they do not change are the fundamental trade-offs that shape agent behavior.

The most successful systems will be hybrid by design. Reflex mechanisms will remain essential for safety and responsiveness, planning and utility-based reasoning will support coordination and optimization and learning will be applied selectively where adaptability is truly required. Teams that succeed tend to start small, constrain scope and expand incrementally based on real-world feedback.

For all the rapid innovation, the core lesson remains the same. Understanding the fundamental types of AI agents helps teams reason clearly, choose deliberately and avoid unnecessary complexity. Tools will evolve, but sound agent design will continue to determine which systems work in production — and which do not.

Automatically Build AI Agents with Databricks

Automatically build an agent

There are platforms, like Databricks Agent Bricks, that provide a simple approach to build and optimize domain-specific, high-quality AI agent systems for common AI use cases. Specify your use case and data, and Agent Bricks will automatically build out several AI agent systems for you that you can further refine.

Author an agent in code

Mosaic AI Agent Framework and MLflow provide tools to help you author enterprise-ready agents in Python.

Databricks supports authoring agents using third-party agent authoring libraries like LangGraph/LangChain, LlamaIndex, or custom Python implementations.

Prototype agents with AI Playground

The AI Playground is the easiest way to create an agent on Databricks. AI Playground lets you select from various LLMs and quickly add tools to the LLM using a low-code UI. You can then chat with the agent to test its responses and then export the agent to code for deployment or further development.

What types of agents can be built using Agent Bricks?

Agent Bricks, a part of the Databricks Data Intelligence Platform, can be used to build several types of production-grade AI agents, which are optimized for common enterprise use cases. The primary agent types supported are:

- Information Extraction Agent: This agent transforms unstructured documents (such as PDFs, emails, reports, etc.) into structured data for analysis.

- Knowledge Assistant Agent: This type creates a high-quality, customizable chatbot that can answer questions based on your organization's specific data and documents (e.g., HR policies, technical manuals, or product documentation), providing citations for its answers.

- Custom LLM Agent: This agent handles specialized text generation and transformation tasks, such as summarizing customer calls, classifying content by topic, analyzing sentiment, or generating on-brand marketing content.

- Multi-Agent Supervisor: This orchestrates multiple specialized agents (and other tools or APIs) to work together on complex, multi-step workflows, such as combining document retrieval with compliance checks.

Never miss a Databricks post

What's next?

Data Science and ML

June 12, 2024/8 min read

Mosaic AI: Build and Deploy Production-quality AI Agent Systems

AI

January 7, 2025/6 min read