Retrieval-based agents are at the heart of many mission-critical enterprise use cases. Enterprise customers expect them to perform reasoning tasks that require following specific user instructions and operating effectively across heterogeneous knowledge sources. However, more often than not, traditional retrieval augmented generation (RAG) fails to translate fine-grained user intent and knowledge source specifications into precise search queries. Most existing solutions effectively ignore this problem, employing off-the-shelf search tools. Others drastically underestimate the challenge, relying solely on custom models for embedding and reranking, which are fundamentally limited in their expressiveness. In this blog, we present the Instructed Retriever – a novel retrieval architecture that addresses the limitations of RAG, and reimagines search for the agentic era. We then illustrate how this architecture enables more capable retrieval-based agents, including systems like Agent Bricks: Knowledge Assistant, which must reason over complex enterprise data and maintain strict adherence to user instructions.

For instance, consider an example at Figure 1, where a user asks about battery life expectancy in a fictitious FooBrand product. In addition, system specifications include instructions about recency, types of document to consider, and response length. To properly follow the system specifications, the user request has to first be translated into structured search queries that contain the appropriate column filters in addition to keywords. Then, a concise response grounded in the query results, has to be generated based on the user instructions. Such complex and deliberate instruction-following is not achievable by a simple retrieval pipeline that focuses on user query alone.

![Figure 1. Example of the instructed retrieval workflow for query [What is the battery life expectancy for FooBrand products]. User instructions are translated into (a) two structured retrieval queries, retrieving both recent reviews, as well as an official product description (b) a short response, grounded in search results.](https://www.databricks.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/image7_24.png)

Traditional RAG pipelines rely on single-step retrieval using user query alone and do not incorporate any additional system specifications such as specific instructions, examples or knowledge source schemas. However, as we show in Figure 1, these specifications are key to successful instruction following in agentic search systems. To address these limitations, and to successfully complete tasks such as the one described in Figure 1, our Instructed Retriever architecture enables the flow of system specifications into each of the system components.

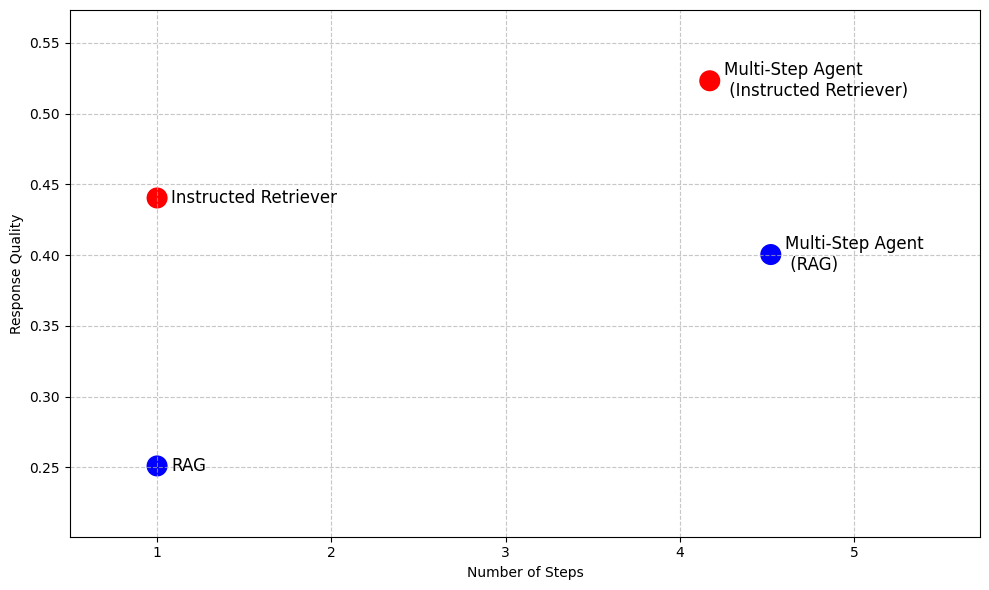

Even beyond RAG, in more advanced agentic search systems that allow iterative search execution, instruction following and underlying knowledge source schema comprehension are key capabilities that cannot be unlocked by simply executing RAG as a tool for multiple steps, as Table 1 illustrates. Thus, Instructed Retriever architecture provides a highly-performant alternative to RAG, when low latency and small model footprint are required, while enabling more effective search agents for scenarios like deep research.

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) | Instructed Retriever | Multi-step Agent (RAG) | Multi-step Agent (Instructed Retriever) | |

Number of search steps | Single | Single | Multiple | Multiple |

Ability to follow instructions | ✖️ | ✅ | ✖️ | ✅ |

Knowledge source comprehension | ✖️ | ✅ | ✖️ | ✅ |

Low latency | ✅ | ✅ | ✖️ | ✖️ |

Small model footprint | ✅ | ✅ | ✖️ | ✖️ |

Reasoning about outputs | ✖️ | ✖️ | ✅ | ✅ |

Table 1. A summary of capabilities of traditional RAG, Instructed Retriever, and a multi-step search agent implemented using either of the approaches as a tool

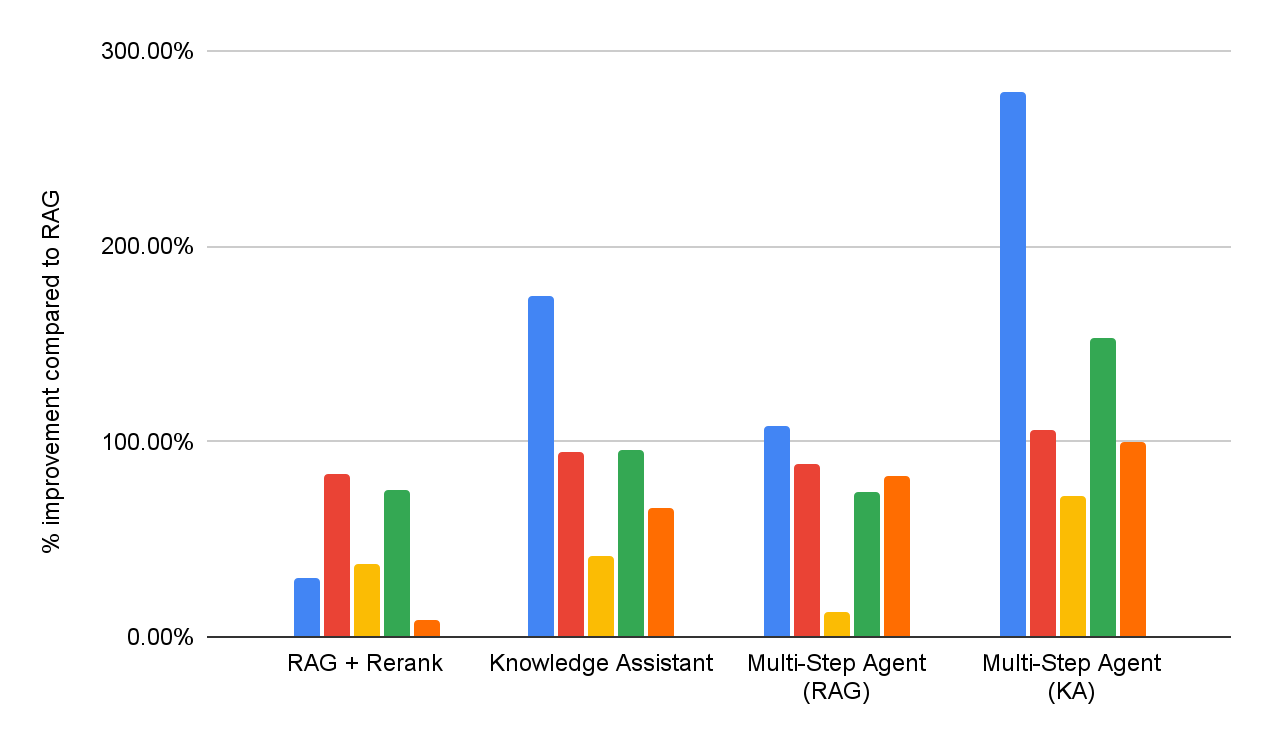

To demonstrate the advantages of the Instructed Retriever, Figure 2 previews its performance compared to RAG-based baselines on a suite of enterprise question answering datasets1. On these complex benchmarks, Instructed Retriever increases performance by more than 70% compared to traditional RAG. Instructed Retriever even outperforms a RAG-based multi-step agent by 10%. Incorporating it as a tool in a multi-step agent brings additional gains, while reducing the number of execution steps, compared to RAG.

In the rest of the blog post, we discuss the design and the implementation of this novel Instructed Retriever architecture. We demonstrate that the instructed retriever leads to a precise and robust instruction following at the query generation stage, which results in significant retrieval recall improvements. Furthermore, we show that these query generation capabilities can be unlocked even in small models through offline reinforcement learning. Finally, we further break down the end-to-end performance of the instructed retriever, both in single-step and multi-step agentic setups. We show that it consistently enables significant improvements in response quality compared to traditional RAG architectures.

Instructed Retriever Architecture

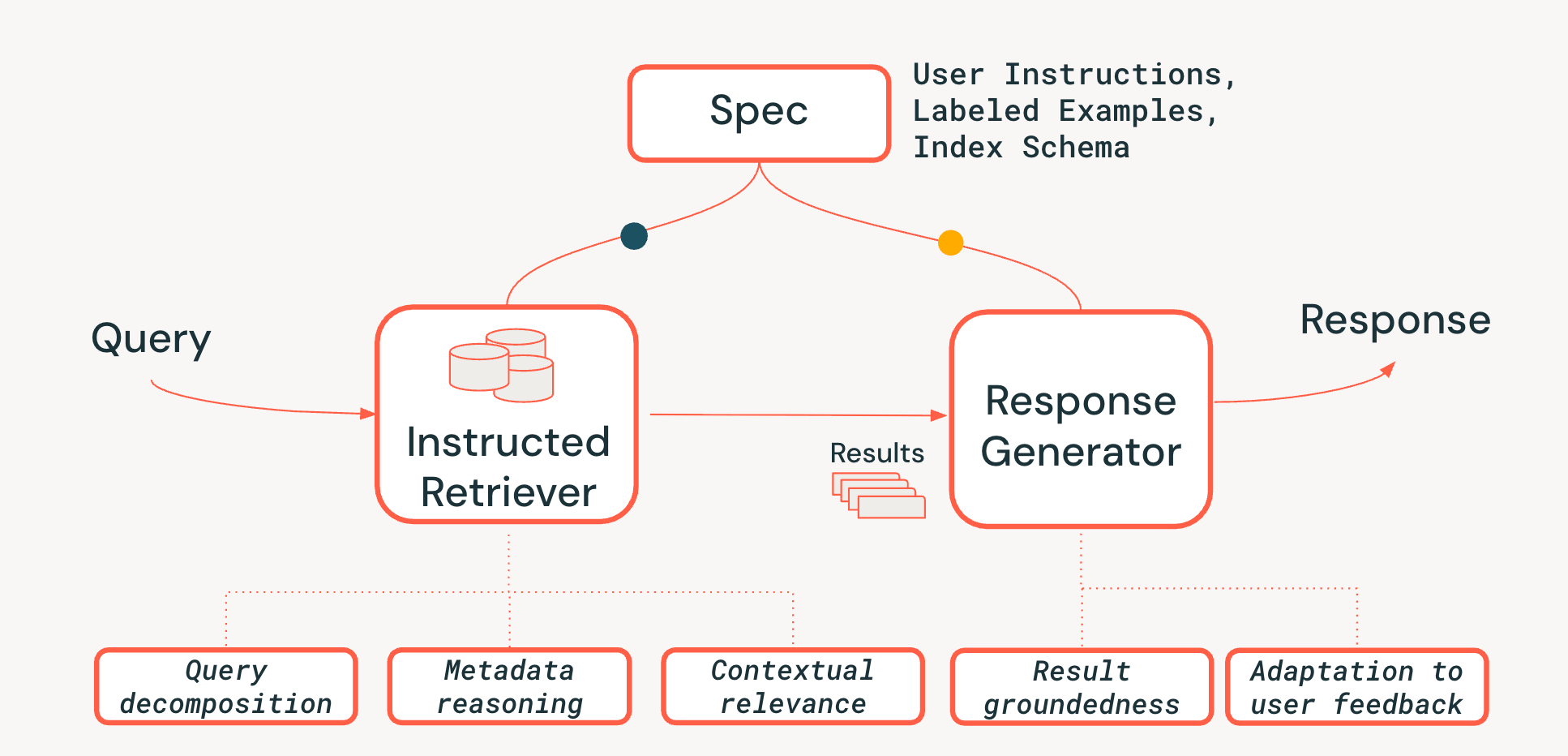

To address the challenges of system-level reasoning in agentic retrieval systems, we propose a novel Instructed Retriever architecture, shown in Figure 3. The Instructed Retriever can either be called in a static workflow or exposed as a tool to an agent. The key innovation is that this new architecture provides a streamlined way to not just address the user's immediate query, but also to propagate the entirety of the system specifications to both retrieval and generation system components. This is a fundamental shift from traditional RAG pipelines, where system specifications might (at best) influence the initial query but are then lost, forcing the retriever and the response generator to operate without the vital context of these specifications.

System specifications are thus a set of guiding principles and instructions that the agent must follow to faithfully fulfill the user request, which may include:

- User Instructions: General preferences or constraints, like "focus on reviews from the past few years" or "Do not show any FooBrand products in the results".

- Labeled Examples: Concrete samples of relevant / non-relevant <query, document> pairs that help define what a high-quality, instruction-following retrieval looks like for a specific task.

- Index Descriptions: A schema that tells the agent what metadata is actually available to retrieve from (e.g. product_brand, doc_timestamp, in the example in Figure 1).2

To unlock the persistence of specifications throughout the entire pipeline, we add three critical capabilities to the retrieval process:

- Query Decomposition: The ability to break down a complex, multi-part request ("Find me a FooBrand product, but only from last year, and not a 'lite' model") into a full search plan, containing multiple keyword searches and filter instructions.

- Contextual Relevance: Moving beyond simple text similarity to true relevance understanding in the context of query and system instructions. This means the re-ranker, for example, can use the instructions to boost documents that match the user intent (e.g., "recency"), even if the keywords are a weaker match.

- Metadata Reasoning: One of the key differentiators of our Instructed Retriever architecture is the ability to translate natural language instructions ("from last year") into precise, executable search filters ("doc_timestamp > TO_TIMESTAMP('2024-11-01')").

We also ensure that the response generation stage is concordant with the retrieved results, system specifications, and any previous user history or feedback (as described in more detail in this blog).

Instruction adherence in search agents is challenging because user information needs can be complex, vague, or even conflicting, often accumulated through many rounds of natural language feedback. The retriever must also be schema-aware — able to translate user language into structured filters, fields, and metadata that actually exist in the index. Finally, the components must work together seamlessly to satisfy these complex, sometimes multi-layered constraints without dropping or misinterpreting any of them. Such coordination requires holistic system-level reasoning. As our experiments in the next two sections demonstrate, Instructed Retriever architecture is a major advance toward unlocking this capability in search workflows and agents.

Evaluating Instruction-Following in Query Generation

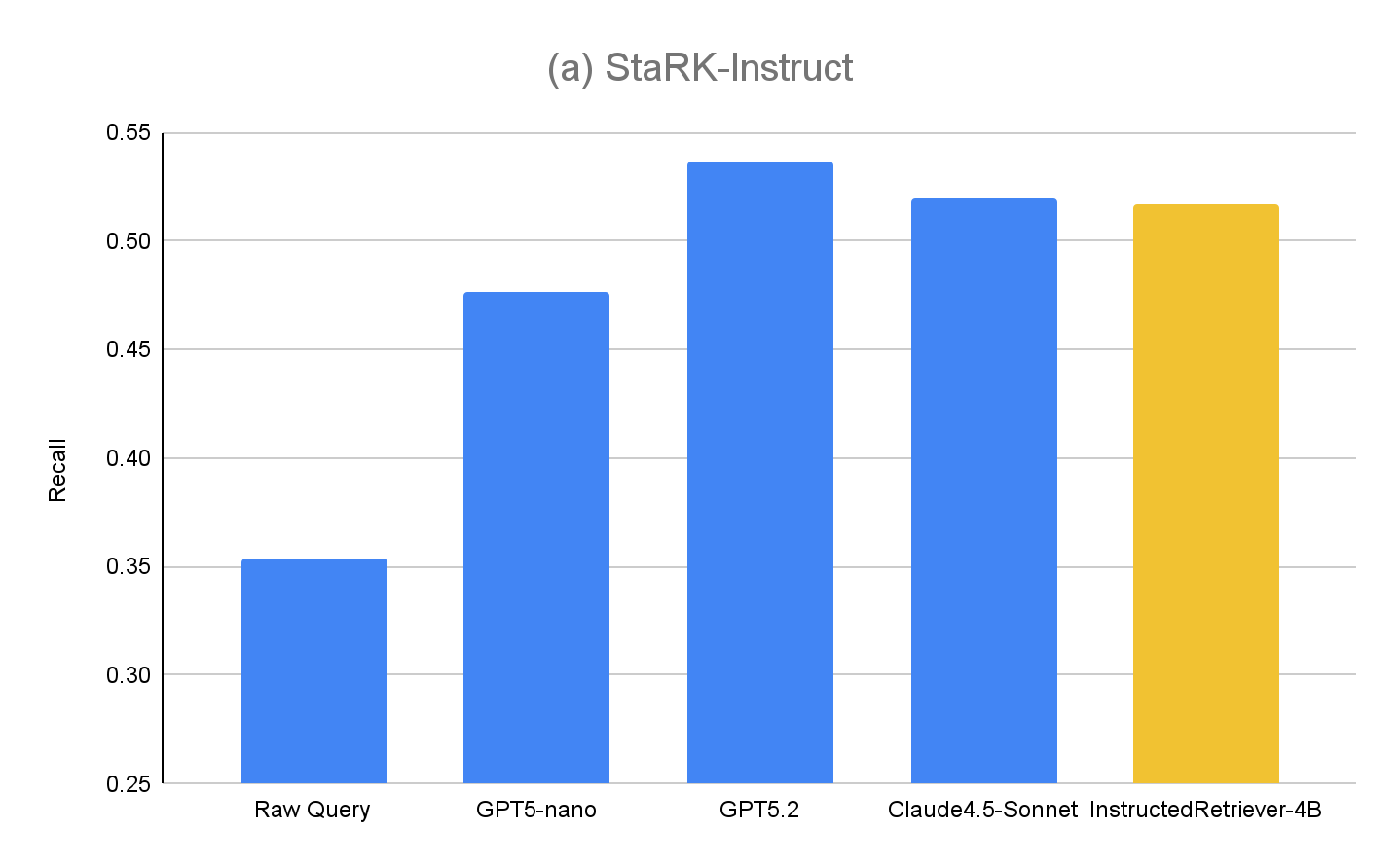

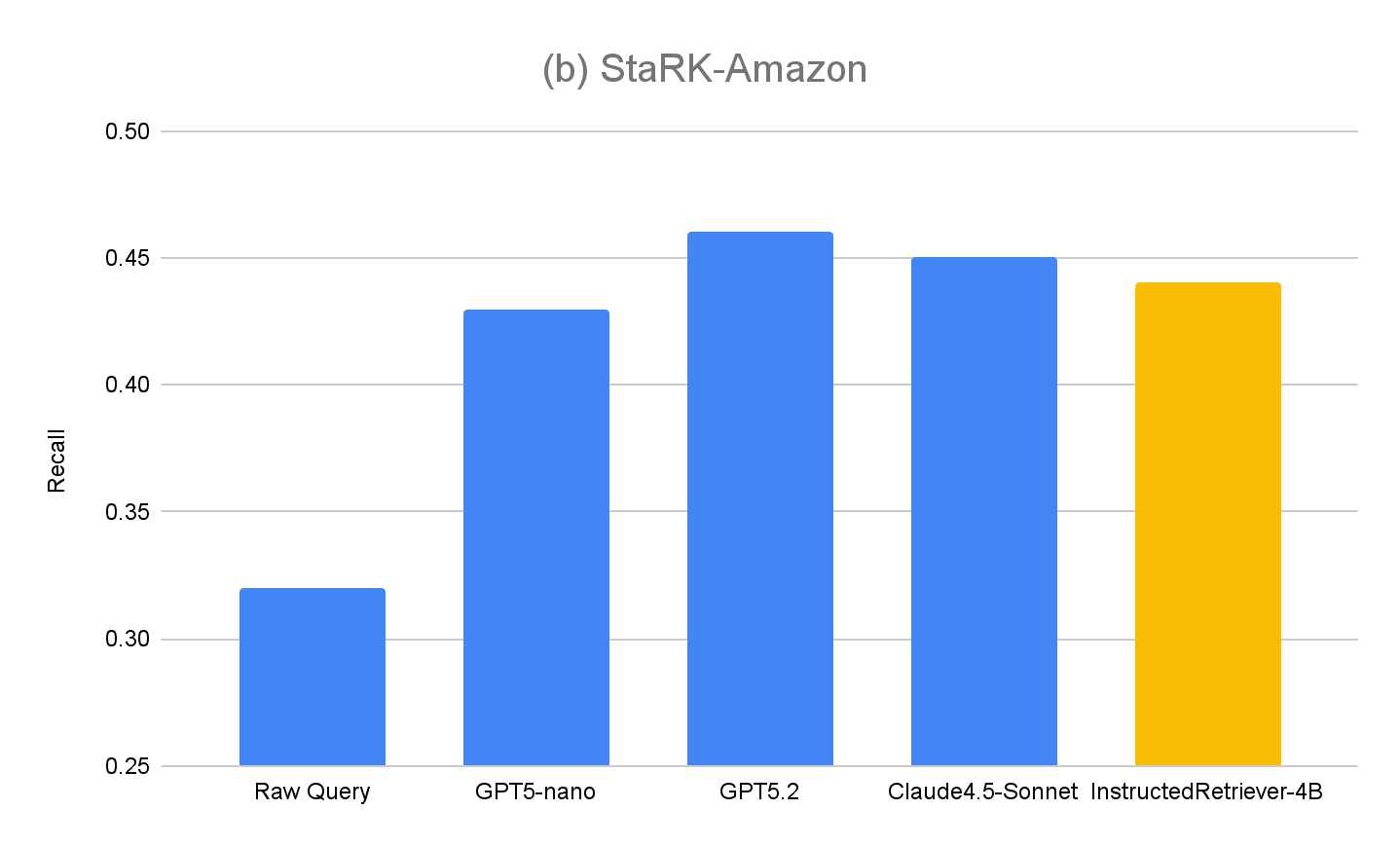

Most existing retrieval benchmarks overlook how models interpret and execute natural-language specifications, particularly those involving structured constraints based on index schema. Therefore, to evaluate the capabilities of our Instructed Retriever architecture, we extend the StaRK (Semi-Structured Retrieval Benchmark) dataset and design a new instruction-following retrieval benchmark, StaRK-Instruct, using its e-commerce subset, STaRK-Amazon.

For our dataset, we focus on three common types of user instructions that require the model to reason beyond plain text similarity:

- Inclusion instructions – selecting documents that must contain a certain attribute (e.g., “find a jacket from FooBrand that is best rated for cold weather”).

- Exclusion instructions – filtering out items that should not appear in the results (e.g., “recommend a fuel-efficient SUV, but I’ve had negative experiences with FooBrand, so avoid anything they make”).

- Recency boosting – preferring newer items when time-related metadata is available (e.g., “Which FooBrand laptops have aged well? Prioritize reviews from the last 2–3 years—older reviews matter less due to OS changes”).

To build StaRK-Instruct, while being able to reuse the existing relevance judgments from StaRK-Amazon, we follow prior work on instruction following in information retrieval, and synthesize the existing queries into more specific ones by including additional constraints that narrow the existing relevance definitions. The relevant document sets are then programmatically filtered to ensure alignment with the rewritten queries. Via this process, we synthesize 81 StaRK-Amazon queries (19.5 relevant documents per query) into 198 queries in StaRK-Instruct (11.7 relevant documents per query, across the three instruction types).

To evaluate the query generation capabilities of Instructed Retriever using StaRK-Instruct, we evaluate the following methods (in a single step retrieval setup)

- Raw Query – as a baseline, we use the original user query for retrieval, without any additional query generation stages. This is akin to a traditional RAG approach.

- GPT5-nano, GPT5.2, Claude4.5-Sonnet – we use each of the respective models to generate retrieval query, using both original user queries, system specifications including user instructions, and index schema.

- InstructedRetriever-4B – While frontier models like GPT5.2 and Claude4.5-Sonnet are highly effective, they may also be too expensive for tasks like query and filter generation, especially for large-scale deployments. Therefore, we apply the Test-time Adaptive Optimization (TAO) mechanism, which leverages test-time compute and offline reinforcement learning (RL) to teach a model to do a task better based on past input examples. Specifically, we use the “synthetized” query subset from StaRK-Amazon, and generate additional instruction-following queries using these synthetized queries. We directly use recall as the reward signal to fine-tune a small 4B parameter model, by sampling candidate tool calls and reinforcing those achieving higher recall scores.

The results for StaRK-Instruct are shown at Figure 4(a). Instructed query generation achieves 35–50% higher recall on the StaRK-Instruct benchmark compared to the Raw Query baseline. The gains are consistent across model sizes, confirming that effective instruction parsing and structured query formulation can deliver measurable improvements even under tight computational budgets. Larger models generally exhibit further gains, suggesting scalability of the approach with model capacity. However, our fine-tuned InstructedRetriever-4B model almost equals the performance of much larger frontier models, and outperforms the GPT5-nano model, demonstrating that alignment can substantially enhance the effectiveness of instruction-following in agentic retrieval systems, even with smaller models.

To further evaluate the generalization of our approach, we also measure performance on the original evaluation set, StaRK-Amazon, where queries do not have explicit metadata-related instructions. As shown in Figure 4(b), all the instructed query generation methods exceed Raw Query recall on StaRK-Amazon by around 10%, confirming that instruction-following is beneficial in unconstrained query generation scenarios as well. We also see no degradation in InstructedRetriever-4B performance compared to non-finetuned models, confirming that specialization to structured query generation does not hurt its general query generation capabilities.

Deploying Instructed Retriever in Agent Bricks

In the previous section, we demonstrated the significant gains in retrieval quality that are achievable using instruction-following query generation. In this section, we further explore the usefulness of an instructed retriever as a part of a production-grade agentic retrieval system. In particular, Instructed Retriever is deployed in Agent Bricks Knowledge Assistant, a QA chatbot with which you can ask questions and receive reliable answers based on the provided domain-specialized knowledge.

We consider two DIY RAG solutions as baselines:

- RAG We feed the top retrieved results from our highly performant vector search into a frontier large language model for generation.

- RAG + Rerank We follow the retrieval stage by a reranking stage, which was shown to boost retrieval accuracy by an average of 15 percentage points in earlier tests. The reranked results are fed into a frontier large language model for generation.

To assess the effectiveness of both DIY RAG solutions, and Knowledge Assistant, we conduct answer quality evaluation across the same enterprise question answering benchmark suite as reported at Figure 1. Furthermore, we implement two muti-step agents that have access to either RAG or Knowledge Assistant as a search tool, respectively. Detailed performance for each dataset is reported in Figure 5 (as a % improvement compared to the RAG baseline).

Overall, we can see that all systems consistently outperform the simple RAG baseline across all datasets, reflecting its inability to interpret and consistently enforce multi-part specifications. Adding a re-ranking stage improves results, demonstrating some benefit from post-hoc relevance modeling. Knowledge Assistant, implemented using the Instructed Retriever architecture, brings further improvements, indicating the importance of persisting the system specifications – constraints, exclusions, temporal preferences, and metadata filters – through every stage of retrieval and generation.

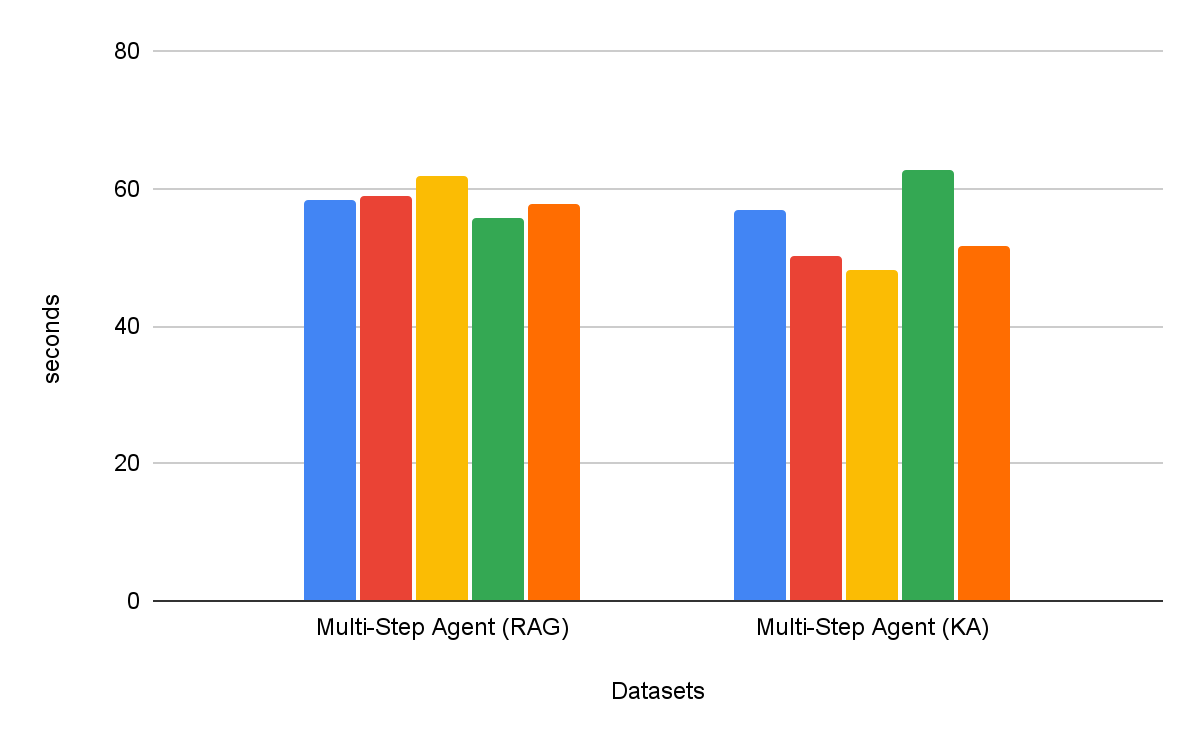

Multi-step search agents are consistently more effective than single-step retrieval workflows. Furthermore, the choice of tool matters – Knowledge Assistant as a tool outperforms RAG as a tool by over 30%, with consistent improvement across all datasets. Interestingly, it does not just improve quality, but also achieves lower time to task completion in most datasets, with average reduction of 8% (Figure 6).

Conclusion

Building reliable enterprise agents requires comprehensive instruction-following and system-level reasoning when retrieving from heterogeneous knowledge sources. To this end, in this blog we present the Instructed Retriever architecture, with the core innovation of propagating complete system specifications — from instructions to examples and index schema — through every stage of the search pipeline.

We also presented a new StaRK-Instruct dataset, which evaluates retrieval agent's ability to handle real-world instructions like inclusion, exclusion, and recency. On this benchmark, the Instructed Retriever architecture delivered substantial 35-50% gains in retrieval recall, empirically demonstrating the benefits of a system-wide instruction-awareness for query generation. We also show that a small, efficient model can be optimized to match the instruction-following performance of larger proprietary models, making Instructed Retriever a cost-effective agentic architecture suitable for real-world enterprise deployments.

When integrated with an Agent Bricks Knowledge Assistant, Instructed Retriever architecture translates directly into higher-quality, more accurate responses for the end user. On our comprehensive high-difficulty benchmark suite, it provides gains of upward of 70% compared to a simplistic RAG solution, and upward of 15% quality gain compared to more sophisticated DIY solutions that incorporate reranking. Furthermore, when integrated as a tool for a multi-step search agent, Instructed Retriever can not only boost performance by over 30%, but also decrease time to task completion by 8%, compared to RAG as a tool.

Instructed Retriever, along with many previously published innovations like prompt optimization, ALHF, TAO, RLVR, is now available in the Agent Bricks product. The core principle of Agent Bricks is to help enterprises develop agents that accurately reason on their proprietary data, continuously learn from feedback, and achieve state-of-the-art quality and cost-efficiency on domain-specific tasks. We encourage customers to try the Knowledge Assistant and other Agent Bricks products for building steerable and effective agents for their own enterprise use cases.

Authors: Cindy Wang, Andrew Drozdov, Michael Bendersky, Wen Sun, Owen Oertell, Jonathan Chang, Jonathan Frankle, Xing Chen, Matei Zaharia, Elise Gonzales, Xiangrui Meng

1 Our suite contains a mix of five proprietary and academic benchmarks that test for the following capabilities: instruction-following, domain-specific search, report generation, list generation, and search over PDFs with complex layouts. Each benchmark is associated with a custom quality judge, based on the response type.

2 Index descriptions can be included in the user-specified instruction, or automatically constructed via methods for schema linking that are often employed in systems for text-to-SQL, e.g. value retrieval.